Ash Barty: Life after tennis by Hugh Lunn

published in The Australian Monday 11 April 2022

They were both childhood tennis prodigies. They both had the best forehand in the world, and each described a deadly sliced backhand. Thus, they were both great at doubles as well as singles. And they grew up at opposite ends of the same street – Ipswich Road, which connects Brisbane’s Gabba with the nearby city of Ipswich.

Not only all that, but they both decided – 60 years apart – to give tennis away in their mid-20s … for the very same reasons. They wanted to do good, and at the same time escape the daily grind.

The must-win matches against powerful opponents. A different hotel room every week for 10 months a year. Away from home, from family, from friends and birthday parties and big weddings and little births.

It’s a bit like living permanently with Covid.

Never being able to be where you want to be when you want to be there. With the few people who understand you. The strict tournament structure – it’s May, I must be in Italy, France and then Germany; it’s June, I have to be in England; it’s March or September, I must quickly head for the United States.

On and on it goes … until it’s finally time to travel to the other end of the earth – Australia, where everything has changed since you were last allowed home. Finally freed from playing tennis six hours a day.

She, of course, is Ash Barty of Ipswich who shocked the whole world when she stepped away from tennis at the height of her powers. Now, she has just announced her new career: children’s book writer – a six-book series about a little tennis player called “Little Ash”. And, like Mary Poppins who brought possibility and hope to children (written by another Queenslander, PL Travers), Barty, with a tennis racquet instead of an umbrella, wants to tour rural Australia reading the books to little children.

He was Ken Fletcher, the son of a train driver called Norm from the working-class south side of Brisbane in a rented house at 524 Ipswich Road, Annerley. His mother, Ethel, had lost four babies and was told she would never have another so she and husband Norm got on with their lonely lives in the midst of World War II. Then, aged 41, Ethel wasn’t feeling well. The doctor announced: “Mrs Fletcher, you’re pregnant!”

“How did that happen?” Ethel wondered aloud.

“I’ll tell you what, it didn’t arrive by telegram,” said the doctor.

Ethel was so happy when she got him home from hospital a week later – in June 1941 – that she tearfully said to Norm: “I hope the Japs don’t get him”.

Their rented home had a falling-down ant-bed tennis court out the back and, being an only child with no siblings, little Kenny hit a tennis ball up against the warped return board for hours. He was too small to hold the racquet properly so he tucked the handle under his armpit and held the racquet by the throat – which meant he had to turn completely side-on to hit his forehand.

Which, unbeknown to him or anyone else at the time, was what gave it so much power.

By the time he was nine, little Kenny was hitting so many forehand winners that – just like Barty – people muttered: “This kid’ll win Wimbledon one day.”

And, just like Ash, that became Kenny’s all-consuming ambition.

At 18 he made the winning Davis Cup squad of six that toured the world for seven months and brought back the cup. At 22 he made the Davis Cup team of four that won the Cup in his home town of Brisbane. In the team with him were three Wimbledon champions: Rod Laver, Neale Fraser and Roy Emerson. Soon he beat Emerson in Sydney and Fraser 6-0 in the fifth in Melbourne.

At 23, Fletch – as he was now called – made the final of the Australian Open without dropping a set. Thus, he was seeded No. 3 at Wimbledon.

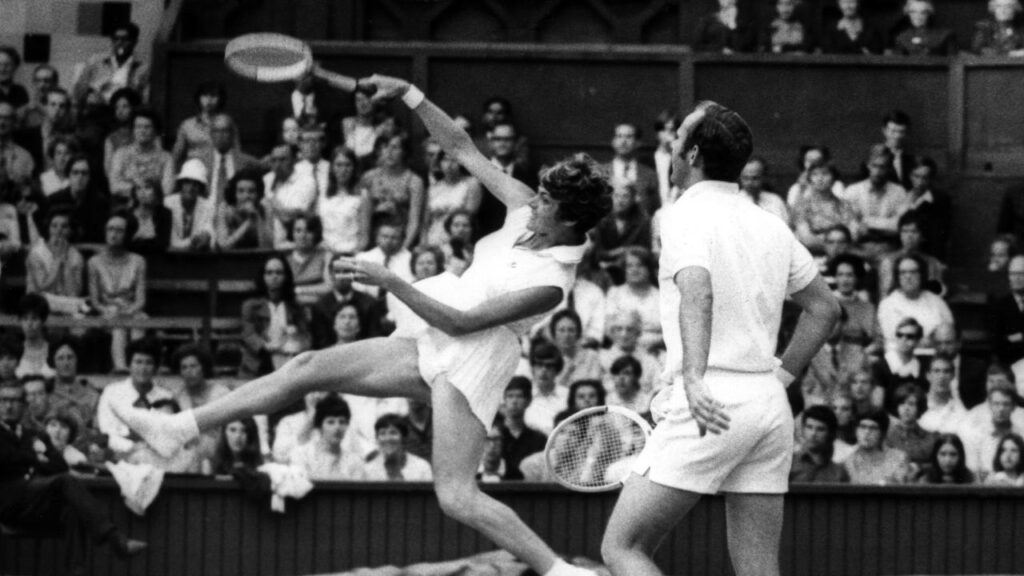

Margaret Smith (Court) could have played the mixed doubles with any champion she liked, but she played with Fletch. That first year they became the first (and still only) pair to win the Grand Slam of mixed doubles in one calendar year – winning the Australian, the French, then Wimbledon and, finally, the US Open.

The world was Kenny’s as he set off for the 1964 world tour with the Australian team.

But after a few months he wrote an aerogram home to me in which he asked me on no account to tell anyone, but he was going to give away “the constant grind” of tennis. He said he couldn’t fall in love – as he had twice in Brisbane – because he couldn’t expect the girls to wait for him to come home and take them out once or twice a year. So he’d missed out there, as he put it.

“Tennis is a knife-fight day after day Hughie,” he wrote. “You can’t be injured because it doesn’t help you. Wanting to win doesn’t help because desperation is what stops you from succeeding.

“I want to do good things for people instead of hitting a little white ball over a net. The secret is: I’m going to apply to study medicine when I get home.”

Of course, tennis was a different game back then from the one Ash Barty played. The racquets were different (timber); the balls were a different colour (white); the strings were different (cat gut); and there were different rules. No “short deuces” and, with no tiebreaks, a set could be won 30-28.

There was no stopping for injuries, either, or “bathroom breaks”. As Fletch said, “If you can yank him around the court until he gets cramps, well, if he can’t continue, you can walk in and wind the net down and the match is yours.”

There were no chairs allowed on the court for a player to sit on. Fletch was reprimanded when he leaned on a wall at the change of ends and Frank Sedgman was admonished when he sat briefly on the steps of the umpire’s stand.

As the umpires announced at the start of every Wimbledon match: “Play shall be continuous.”

Fletch had a very good academic record at school because Norm made him do his homework in what was a quiet, lonely household where his parents – now pensioners – listened to the wireless every night. But tennis commitments meant he hadn’t competed Grade 12 – and the University of Queensland wouldn’t accept him for medicine.

I could see that the trouble with becoming a champion sportsman, or woman, is that while you’re playing until the age of 25 everyone else has already become a physiotherapist, a doctor, a chemist, Australia’s chief censor, a rising public servant – as had Ken’s classmates at St Lawrence’s College in Brisbane.

But you are not qualified for anything, except coaching.

Fletch definitely didn’t want to coach tennis. So maybe he could become a public relations man for a big hotel – seeing as how he had stayed in so many? In fact, the Grand Hotel in Hong Kong had said he could stay for nothing if he ever came to live in Hong Kong.

However, the lonely only child didn’t want to be lonely in a hotel room all over again. He asked me if I would go to Hong Kong with him because “Hong Kong is full of girlfriends” – so I went.

Ken had no experience in public relations – and couldn’t speak Cantonese – so Mr Sun, the owner of the Grand Hotel, said we could stay on if Ken coached his son Victor to win the Hong Kong tennis championship. For a couple of hours every day Ken hit with Victor and at night we went to the pictures or one of the many Hong Kong nightclubs until very late.

Ken was pleased not to have to play all the state titles and the Australian Open that year – and, also, he had decided to never again play the US Open because he said “it lacks class”. But he did fly over and win the Philippines national title; and on Christmas Day he insisted we take out a group of orphans from St Paul’s Jesuit Orphanage, Causeway Bay, for the day.

After that he gave money to the orphanage and even tried to teach English there once or twice over the years.

After spending almost a year away from tennis, he decided he’d give Wimbledon one last try aged 25. But he ran into the winner that year, Roy Emerson, and after so many months in nightclubs, he faded. He had served for the fourth set at 9-8 but lost 10-8, 6-4,3-6, 11-9.

He was the only player to win a set off Emerson.

He left the Hong Kong nightclubs and went back again to Wimbledon in 1966 where on the Centre Court he served for the match at 5-4 in the fifth in the quarter-final against the eventual winner, Manuel Santana of Spain. But he won the men’s doubles with John Newcombe as a scratch pair when Tony Roche rolled his ankle (they won a 10-pound voucher to Lilywhite’s store – it was the amateur era). And he once again won the Wimbledon mixed doubles with Margaret Court – so that the BBC’s voice of Wimbledon, John Barrett said: “In the 1960s Ken Fletcher made Wimbledon Centre Court his own.”

Meanwhile, Ken tried to make himself a career in the Far East. He tried exporting beaded cardigans in various colours to Uganda, but that didn’t work. He went to Macau to become a professional gambler, and did his dough.

He had a go at commentating on tennis for the BBC, but after a glitch where he asked, on-air, “Where’s the dunny around here?” he was not invited back. So, with his Pakistani mate Farid Khan, he went to dig for emeralds up beyond the Khyber Pass but found the place “frightening” and they left.

He then sent Farid to Coober Pedy to buy opals to sell in Germany, but a robber broke into the motel room in the dead of night to steal the bag of opals. Farid, an Olympic hockey player, jumped the robber, saved the opals, but his throat was cut open and all the air was bubbling out. The Flying Doctor flew him to Adelaide with the nurse saying: “Don’t worry, Mr Khan: only the good die young”. She was right.

Fletch couldn’t escape his tennis past. He lived in England as a member of the exclusive Wimbledon Club for 20 years. As one Aussie mate said: “It takes five generations of grovelling for an Englishman to meet the sort of people Ken mixes with.”

When he came home to Brisbane on May 7, 1992, Fletch brought with him an old Hong Kong friend, an American philanthropist who had decided to do good – to give away his billions in his own lifetime, what he called “the RAT Theory – Remaining Allocated Time”.

“You’ll have to give some in Brisbane, well,” Ken told him.

When Chuck and Helga Feeney arrived with Ken, Chuck pulled me aside and said: “The boy is very Brisbane-oriented – I’d even say Annerley-oriented. I thought he should come home.”

Chuck bought Ken a penthouse at Kangaroo Point and employed him for the rest of his life – visiting twice a year. In the end, Chuck donated $550m to science and medicine in Australia, most of it in Kenny’s Brisbane.

So there is plenty of life to be lived and plenty of good to be done without hitting a ball over a net.

Ash Barty knows that, and she and Little Ash have already started.

Hugh Lunn is the author of the biography The Great Fletch (HarperCollins).